Trinity DARE Goal Five:

Trinity Self-Examination and Change

To be credible, work in promotion of racial equity must include institutional self-examination and commitment to change. Trinity DARE will include examination of Trinity’s history and current context for promotion of racial equity in all areas of institutional life.

The Trinity History Project: with the engagement of historians on the faculty and others, Trinity will undertake an examination of institutional history on racial equity and related issues. This project should include engagement of Trinity alumnae, Sisters of Notre Dame, and others who can contribute oral histories, documentary material and relevant commentary.

- Faith in Women, poster above, is an exhibit resulting from some of the early work in the Trinity History Project. The exhibit is on display in the Payden Center as part of the 125th Anniversary events.

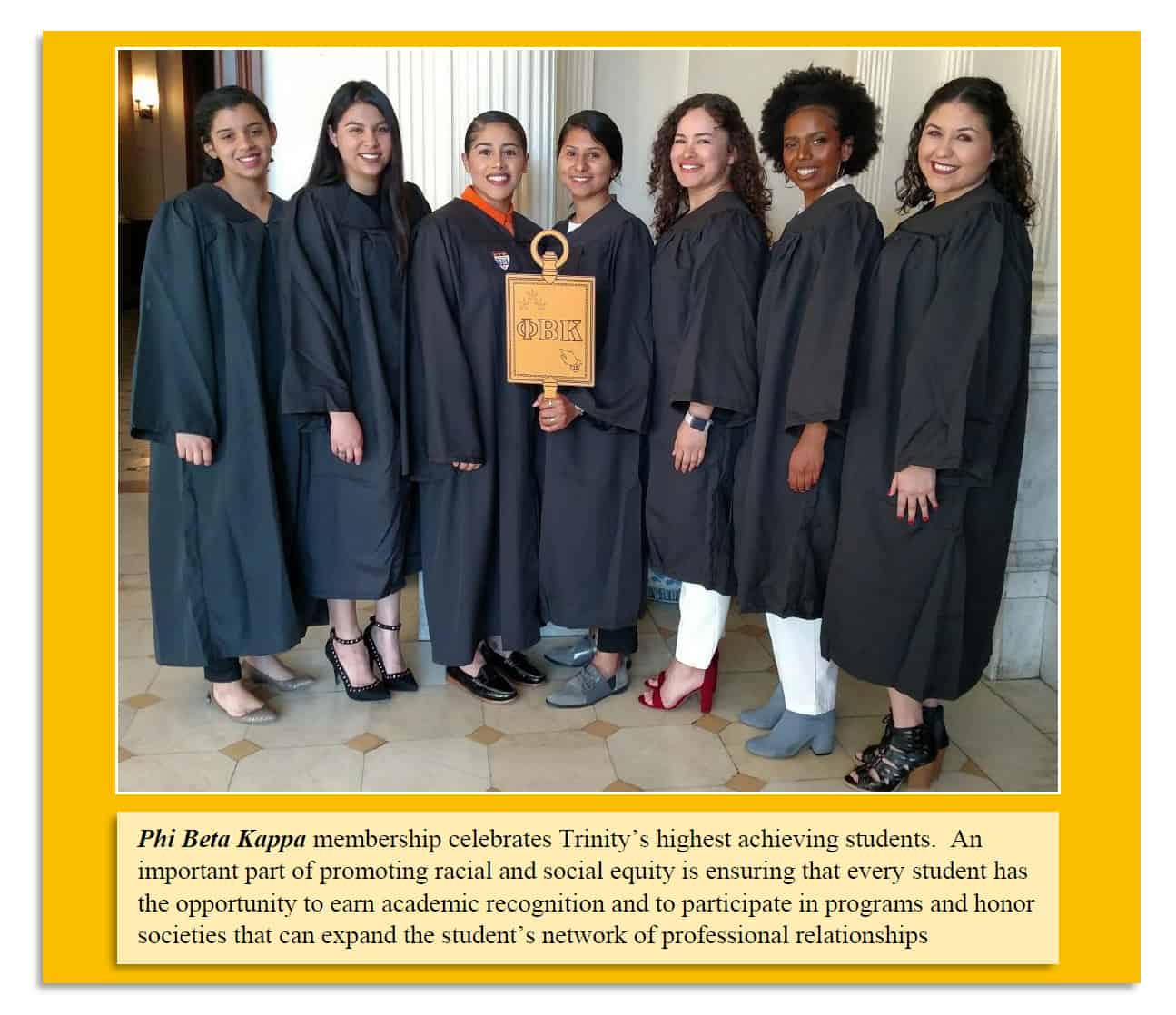

Examining Policies and Practices: Trinity will create a framework for evaluating current policies and practices to ensure fulfillment of racial equity principles. Some of the issues that this part of the project might examine include review of criteria for honors and awards at graduation; criteria for honor societies; disciplinary policies and practices; employment practices and policies.

Trinity: Leading Racial and Social Equity in Higher Education

When the Sisters of Notre Dame founded Trinity in 1897 to relieve Catholic University of the “embarrassment” of refusing admission to women (per the letter of Cardinal James Gibbons to Sr. Julia McGroarty approving the establishment of Trinity), the entire idea of women’s collegiate education was new and cause of alarm at least among some critics both inside and outside of the Catholic Church. Conservative priests at Catholic University caused a storm of criticism that made it to the public press, with some even accusing the sisters of committing heresy. Soon, the controversy reached the Vatican, and the whole project was in danger of termination before the property was even purchased. But with resilience, courage, and smart political insights, Sr. Julia and her colleague Sr. Mary Euphrasia Taylor persisted and persuaded their superiors and even the Pope that the establishment of Trinity as the nation’s first Catholic liberal arts college for women was truly a worthy cause for the Church and humankind.

Fierce advocates for women’s right to a higher education equal to that of men in that day, the SND leaders organized advocates, raised money and bought the land where the first grant building known as Main Hall would soon rise. The first nineteen students arrived on a cold rainy day in 1900, the Red Class of 1904, and the remarkable work of Trinity was underway.

But Sisters Julia and Mary Euphrasia, and the other SNDs and their supporters, were actors in a time and place in American and Church culture that was inherently racist. Only elite white women had the time, money and status to enroll. Trinity was founded a year after the Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) made racial segregation the law of the land, a tragic coda to the terrible prior 30 years of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow. Catholics also suffered virulent discrimination in those days, and Catholic colleges were founded because (as with the founding of women’s colleges and Historically Black Colleges) their students were not welcome elsewhere. The founding of Trinity was a real breakthrough for Catholic women at the turn of the 20th Century, but it would take another half century or more before the first Black students enrolled.

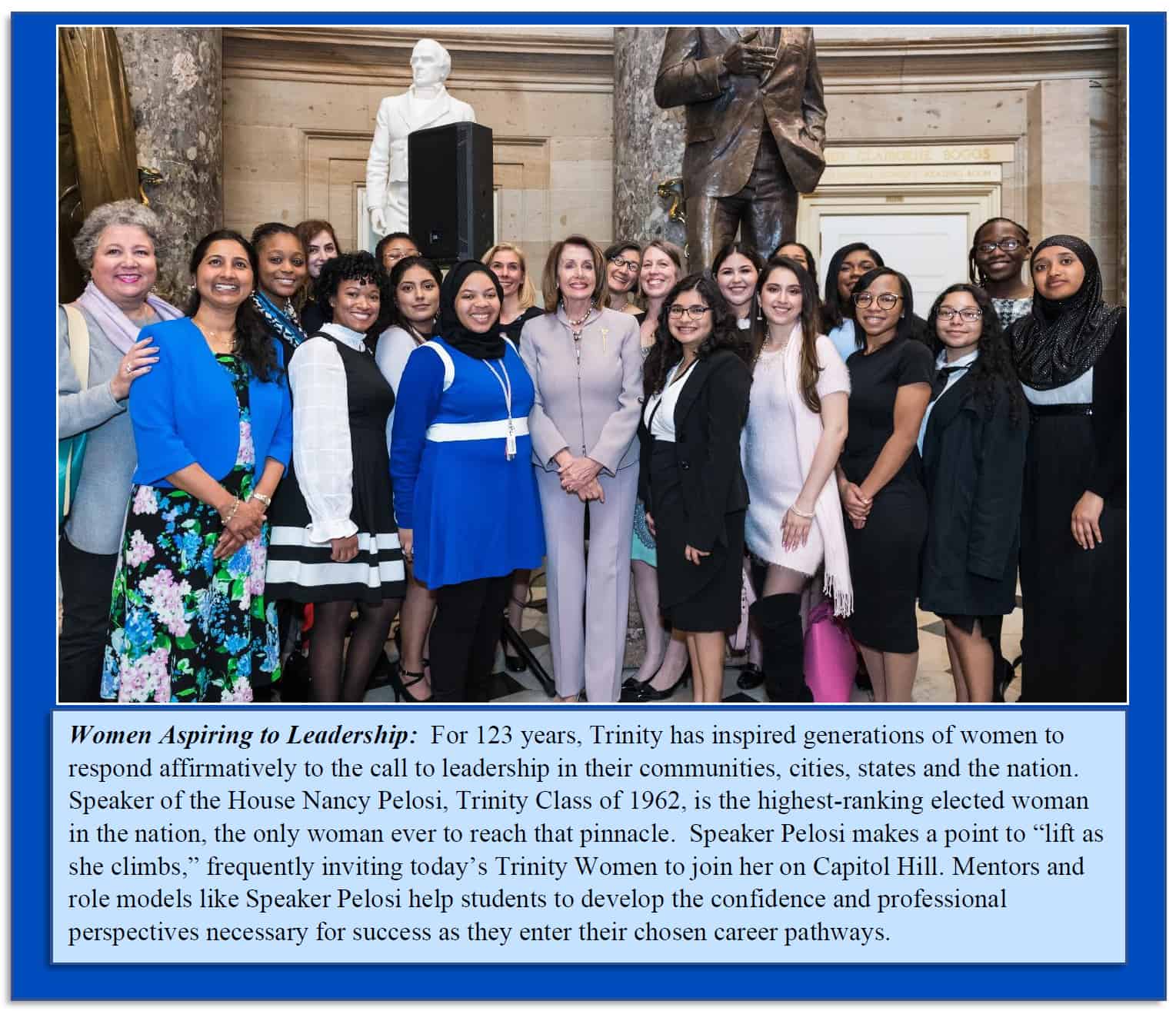

The history of Trinity’s transformation in the latter decades of the 20th Century and into the 21st is an important piece of the study of Trinity’s history that will occur as part of the Trinity DARE project. With a paradigm shift in the demographics of the student body, an equally radical transformation of curricula and pedagogy began to occur in the 1990’s and is ongoing today. But even more important, the transformation of Trinity required deep and profound change in the dispositions of the numerous constituencies who claimed Trinity as their own. Students, alumnae and alumni, faculty and staff, trustees and benefactors, neighbors and friends — all faced the challenge of change and growth in an institution they loved, a challenge to embrace the idea that for Trinity to thrive in future generations, the current inhabitants of the place must learn to practice anti-racism and promote racial equity as essential for this learning community to endure.

Trinity has received much affirmation and support for its transformation to date as the next section of this paper illustrates. However, despite Trinity’s progress over the last several decades, much work remains to ensure that Trinity’s leadership in promoting racial and social equity continues for new generations.

Will you take the Trinity DARE? That is the question this project asks of each participant. Together, we will make Trinity approaching the mid-21st Century a model for practicing anti-racism, achieving racial equity and true justice in all of our endeavors.

Go to Resource Requirements and Funding Opportunities

OR